The Sacrifice of Praise

Stage or Altar in Light of Psalm 50?

In the quiet hush of an Orthodox church, as the incense rises and the faithful stand before the altar, I often reflect on the words of Psalm 501, a cry from King David’s heart after his great fall: “Offer to God a sacrifice of thanksgiving, and pay your vows to the Most High; and call upon me in the day of trouble; I will deliver you, and you shall glorify me... The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise. […] Then shalt Thou be pleased with a sacrifice of righteousness, with oblation and whole-burnt offerings. Then shall they offer bullocks upon Thine altar.” (Psalm 50:14-15, 17, 21). These verses pierce through the veil of outward religion, reminding us that true worship isn’t about grand gestures or fleeting emotions, but about offering our sick and broken selves to a merciful God. It’s a theme that has reshaped my own spiritual journey—from the structured, testimony-driven meetings of my LDS upbringing, where emotional highs often served as epistemic witness to divine presence, to the ancient rhythms of the Orthodox liturgy, where worship demands humility and sacrifice.

My path from Mormonism to Orthodoxy wasn’t a rejection of sincere faith but a deepening hunger for something more rooted, more authentic, and more eternal. In LDS services, I appreciated the focus on family, community, and heartfelt sharing—much like the vibrant energy in many Evangelical gatherings, where contemporary music and relatable preaching draw people in with accessibility and zeal. After all, both traditions spring from a shared love for Christ and a desire to live out His gospel. Evangelicals bring an infectious enthusiasm that makes faith feel immediate and personal, while Orthodox Christians emphasize the unbroken continuity of the apostles’ teaching. Even Brigham Young, a foundational LDS leader, echoed this inward focus when he taught that “true religion is to save souls,” emphasizing not just outward ordinances but the transformation of the heart. Yet, as Psalm 50 warns against superficial offerings—“I will accept no bull from your house, nor he-goat from your folds” (v. 9)—it urges us to examine whether our worship truly honors God or caters to our own ego and comforts.

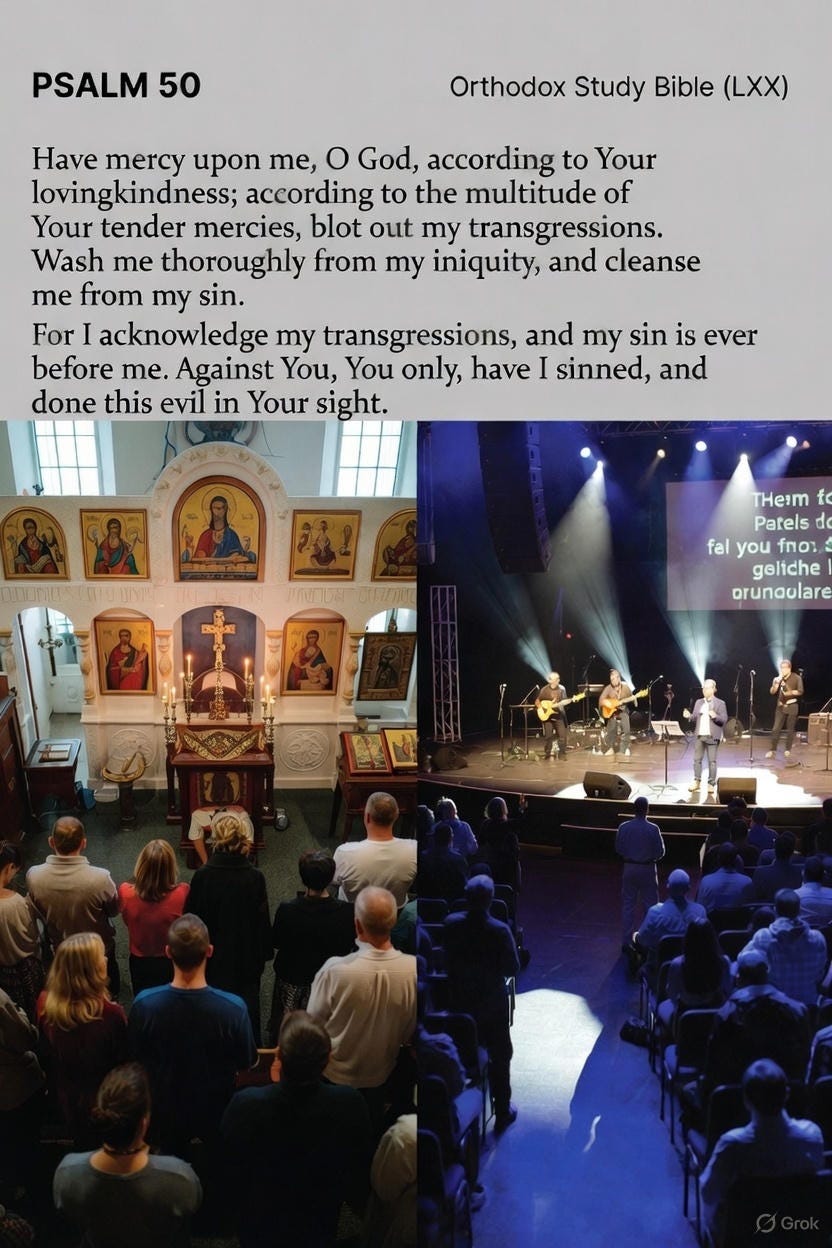

Following the spiritual themes of Psalm 50, which rejects empty sacrifices in favor of a contrite heart. It seems to me that Modern American worship often features a stage that elevates man while catering to individualism and entertainment.2 In contrast, the Orthodox liturgy centers on an altar for all participants, which demands a humble offering to Christ. As we’ll explore, this shift in worship styles arose from cultural pressures such as American consumerism and revivalism, creating emotional experiences that simulate—but cannot replace—the Holy Spirit’s true work.

Saint John Chrysostom, in his profound homily on this psalm, reminds us: “God seeks not the outward act, but the inward disposition of the heart.” Similarly, A.W. Tozer, a revered Evangelical voice, cautioned: “Worship is no longer worship when it reflects the culture around us more than the Christ within us.”

In the sections ahead, we’ll delve into the symbolism of Stage versus Altar—how the former, born of 19th-century revivalist techniques and modern seeker-sensitive models, prioritizes attraction and emotionalism through lights, music, and comfort, while the latter echoes Psalm 50’s call to stand in vigilant sacrifice.

We’ll trace the altar’s ancient roots in Scripture and patristic tradition, contrasting it with the consumer-driven evolution of modern American worship. Finally, we’ll consider sermons as TED-talk style inspirations3 rather than homilies that serve the Eucharistic mystery, while weaving in Psalm 50’s timeless plea for authenticity. Through this lens, may we rediscover worship not as something we consume, but as the offering of our broken hearts to the One who heals them.

Stage or Altar? What are we oriented towards?

In the light of Psalm 50, where David cries out, “Have mercy upon me, O God, according to Your great mercy; according to the multitude of Your compassions, blot out my transgressions” (v. 1), we’re invited to ponder the heart of our worship: Is it a spectacle shaped by our desires to feed our sense of self and ego, or a humble sacrifice directed to Christ? This psalm, the quintessential prayer of repentance in Orthodox tradition, strips away the facade of external rituals, demanding instead that we “create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me” (v. 10). It’s a divine call to authenticity, rejecting superficial piety in favor of a “broken spirit, a broken and a contrite heart—these, O God, You will not despise” (v. 17)—a theme that resonates deeply when we compare the stage-centered approach of modern American worship services with the altar-focused liturgy of Orthodoxy.

Picture a modern protestant gathering: The lights dim, a band takes the stage, and the music swells with emotive chords designed to stir one's emotions and trigger an Elevation Emotion4 response. The preacher strides forward, microphone in hand, delivering a message that feels personal, motivational, and immediately applicable. There’s undeniable beauty here—the passion, the accessibility, the way it draws people in like a welcoming embrace. Evangelicals, with their emphasis on personal faith and Scripture’s transformative power, have mastered making their services feel relevant in a fast-paced world. It's one of the primary reasons evangelical Protestantism is so successful in growing around the world, in places like Iran and China. As John Piper, a prominent Evangelical theologian, wisely notes, “Worship is not about us; it’s about God”—a truth that echoes Psalm 50’s plea for inner renewal over outward show. Yet, in practice, the stage can shift the focus. It elevates performers—worship leaders as artists, preachers as speakers—and creates an audience dynamic where the congregation consumes rather than offers. How American.

This didn’t emerge in a vacuum. Its roots date to the 19th-century American revivalism of figures like Charles Finney, who introduced “new measures” to spur conversions: emotional appeals, prolonged meetings, and techniques to draw crowds in an era of growing secularism and individualism. Finney himself argued that “religion must be made exciting” to compete with worldly distractions, setting the stage—literally—for modern adaptations. Fast-forward to the late 20th century, and the seeker-sensitive model, popularized by leaders like Rick Warren in his book The Purpose-Driven Church5, amplified this. Warren emphasized ministering “in a style that fits the 21st century6,” urging churches to adopt consumer-friendly elements—professional lighting, contemporary music, and TED-talk sermons—to attract unchurched people in a marketplace of ideas. In America’s consumer-driven society, where individualism reigns, and churches compete like brands for attendance, this makes strategic sense. It taps into some of the deepest parts of human emotion and psychology; human impulses for community, inspiration, and emotional release, hooking new attendees with an experience that rivals secular entertainment. But as Psalm 50 warns, “For I acknowledge my transgressions, and my sin is always before me” (v. 3)—such approaches risk becoming the very empty piety God calls us to transcend, more about our ego and comfort than His mercy.

Here’s where the danger of false emotionalism creeps in. The staging—pulsing lights, fog machines, crescendoing music—can manufacture emotional highs that mimic the Holy Spirit’s presence: goosebumps, tears, a rush of warmth. It’s designed to evoke feelings of transcendence, drawing on very human emotions and motivations, such as belonging and catharsis. In the short term, it works brilliantly, encouraging return visits much like a concert or motivational seminar.

Yet, as St. Symeon the New Theologian cautions, “Do not be deceived by sensible delights; true grace comes with compunction, not fleeting ecstasy.” This isn’t the quiet, convicting fire of Pentecost (Acts 2:3), but a simulated spark that fades, leaving attendees chasing the next high rather than cultivating a contrite heart. Even Joseph Smith, in early LDS teachings, spoke of emotional experiences as signs of truth—“If it had not been so, the Holy Ghost would not have come upon them”—yet even he warned against unchecked enthusiasm without substance, a parallel caution for any tradition relying on manufactured fervor. Personally, I'm inclined to draw an additional connection. Looking back on my recent series on the ongoing spiritual warfare between Christ, his Church, the Devil, and the Demons (link below)

The War Unseen: The Long Battle Against Christ and His Church

Author's Note: What follows is a personal hypothesis. While I am a devoted member of the Orthodox Church, this work does not reflect the official position of the Orthodox Church nor does it speak on behalf of it.

We have seen clearly that one of the greatest tactics the Demons employ is counterfeiting divine truth, and I personally would hold that any simulation of the "feeling” of the "holy spirit” is a counterfeit, regardless of whether it's a “burning in your bosom", or a feeling that "the spirit is moving” or a "manifestation of the spirit” brought about by a pastor and the choice of music. The very fact that these emotions are referred to as the spirit or the Holy Spirit seems to illustrate my point. Unfortunately, most people cannot tell the difference between their own emotions and the actual holy spirit. Likewise, most are unaware that these feelings are often manufactured (often on purpose) by church pastors and worship leaders.7 However, a quick poll of recent converts in my parish who came from Baptist, Pentecostal, and other evangelical backgrounds seems to indicate that those who spend enough time in these types of churches eventually realize that what they are feeling is really their own emotions. When they realize that, they begin to see their current experience as shallow and start looking for something more meaningful. LDS usually have very different motivations/triggers - usually to do with LDS church history and the veracity of truth claims.

Contrast this with the Orthodox altar: No spotlights, no performers facing the crowd. The priest stands with his back to the people, all oriented eastward toward Christ, symbolizing our collective pilgrimage to the heavenly Jerusalem. The altar isn’t a platform for self-expression but the mercy seat of sacrifice, where the Eucharist—the Body and Blood of Christ—fulfills the plea of Psalm 50: “Deliver me from bloodguiltiness, O God, Thou God of my salvation, and my tongue will sing aloud of Thy deliverance” (v. 14). Here, worship demands participation and sacrifice, not spectatorship. The only thing that is raised is the sanctuary containing the altar. We stand for much of the Divine Liturgy, echoing the ancient practice described by St. Basil the Great: “We stand during prayer to show that our minds are lifted up to God, as slaves redeemed from bondage.” This posture isn’t about discomfort for its own sake but about embodying Psalm 50’s broken spirit—vigilant, humble, offering our bodies as “living sacrifices” (Romans 12:1). In a world obsessed with ease and entertainment, standing reminds us that, as Jesus taught, true worship must be “in spirit and truth” (John 4:24), not tailored to our mortal impulses.

My 2 Cents Opinion (I say 2 cents because that's about all it's worth, I'm obviously biased, feel free to disagree…)

In Psalm 50’s unrelenting call for repentance, the stage may draw us in with its appeal to individualism and emotional release, but the altar redirects us outward, upward—to Christ alone.

I'm not saying that these emotional experiences are totally evil, unimportant, or without a place. I think that while they may be very good places to start, it's not necessarily the best places to end up. I view faith as a bit of a journey. God meets us where we are, but then we need to be constantly seeking him in ever more discerning ways, even if that leads us to new places that might initially make us a bit uncomfortable. (for God's ways are not our ways.)

Contemporary Protestant worship services and LDS "sacrament” services have a place. These practices can be highly effective in drawing people into the Christian faith, often leading them to abandon heresies or false religions in the process, and that is something worth doing. (Is it ethical? 🤷🏽♂️ I don't know, that's an entirely different question.)

If salvation is in fact theosis, then Protestantism/Mormonism, with its appeal and catering to the ego and our emotions, might open the gate, but then each of us needs to get on the straight and narrow path and “hold to the iron rod” in the face of the "great and spacious building” (LDS audience reference) which may acutally include mainstream christians, our old church or ward, or anything else that mocks or prevents us from making the changes in our lives that bring us closer to God.

What if, in heeding David’s plea, we ask ourselves: Does our worship foster a clean heart, a broken heart, and a contrite spirit? Or does it merely seek entertainment and an emotional fix?

The ancient Church, from the catacombs to the councils, gathered around altars precisely because they understood this: Mercy, sacrifice, not spectacle, draws us into divine communion.

The Ancient Roots of the Altar—Why It Matters

As Psalm 50 implores, “Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin” (v. 2), it beckons us to trace the roots of authentic worship back to their sacred origins—a cleansing not of outward forms but of the heart’s deepest longings. This psalm, David’s profound lament after his transgression with Bathsheba, isn’t just a personal confession; it’s a blueprint for repentance that exposes the futility of ritual without renewal. “For You do not desire sacrifice, or else I would give it; You do not delight in burnt offering” (v. 16), God declares through the prophet-king, pointing us beyond mere externals to the altar of a contrite spirit. In this light, the Orthodox altar stands as a timeless anchor, its importance woven into the fabric of salvation history.8

The altar’s ancient roots run deep, drawing from the Old Testament’s sacrificial system that prefigures Christ’s ultimate passover offering. In Exodus 20:24, God commands, “An altar of earth you shall make for Me, and you shall sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your peace offerings”—a physical space where heaven touched earth, symbolizing atonement and communion. This culminated in the Temple altar, where the high priest entered the Holy of Holies once a year, sprinkling blood for the people’s sins (Leviticus 16). Yet, as Psalm 50 reveals, even these were shadows: “Against You, You only, have I sinned, and done this evil in Your sight” (v. 4)—true atonement demands the heart, not just the rite. The Church Fathers saw this fulfilled in Christ, the Lamb who “takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29). Saint Ignatius of Antioch, writing around 107 AD, urges the early Christians: “Come together in common... breaking one Bread, which is the medicine of immortality, and the antidote which wards off death but yields continuous life in union with Jesus Christ.” For him, the altar was no mere table but the locus of the Eucharist, where believers partake of Christ’s Body and Blood, enacting Psalm 50’s plea: “Restore to me the joy of Your salvation, and uphold me by Your generous Spirit” (v. 12).

By the post-apostolic era, as underground house churches gave way to dedicated basilicas after Constantine’s Edict of Milan in 313 AD, the altar became the undisputed heart of worship. Saint John Chrysostom, in his homilies, describes the liturgy as a heavenly banquet at the altar, where “angels stand by, and the cherubim too... as we partake of the sacred oblation.” This wasn’t innovation but continuity—the altar embodied the mystery of incarnation, sacrifice, and resurrection, countering the Gnostic heresies that divorced spirit from matter. In Orthodoxy today, it remains veiled behind the iconostasis, a reminder of the Holy of Holies, inviting the faithful to approach with fear and trembling, as St. Cyril of Jerusalem warns in his Mystagogical Catecheses: “Approach with awe, for you are about to touch that which even angels tremble to behold.” Here, Psalm 50’s contrition finds its fulfillment: The altar is where we offer our brokenness, receiving in return the “medicine of immortality” that cleanses and renews.

American Protestants, in their sincere pursuit of biblical purity, moved away from altars during the Reformation—a shift rooted in valid critiques of roman catholic corruption, but amplified by later cultural forces. Martin Luther and John Calvin, reacting to perceived Catholic excesses, elevated the pulpit over the sacrament, emphasizing preaching as the primary means of grace. Because they recognized they had no spiritual or priesthood authority or legitimacy for what they were doing. They based all spiritual legitimacy on the Bible in a way that has almost made the Bible an idol. Their epistemology is based on the Bible - that's the core root of Sola Scriptura.

Calvin declared, “The pulpit is the throne for the word of God,” prioritizing the proclaimed Gospel to foster personal conviction. This made sense in an age of corruption, aligning with Psalm 50’s disdain for empty rituals: “You hide Your face from my sins, and blot out all my iniquities” (v. 9). Yet as American revivalism took hold in the 19th century, individualism and consumerism further reshaped this. Preachers like Dwight L. Moody adapted services to compete with urban entertainment, using simple stages and emotional hymns to draw crowds. By the megachurch era, influenced by business models, churches like Willow Creek, under Bill Hybels, adopted seeker-sensitive strategies: “We have to remove every possible obstacle to an unchurched person’s coming to Christ,” Hybels said, a noble goal but one that unfortunately led to consumer-friendly designs that prioritize comfort and appeal. In a society where faith must vie with Netflix and self-help seminars, this hooks attendees through relatable experiences—but, as A.W. Tozer lamented, “The church has surrendered her once lofty concept of God and has substituted for it one so low, so ignoble, as to be utterly unworthy of thinking, worshipping men.”9

"The message of this book does not grow out of these times but it is appropriate to them... I refer to the loss of the concept of majesty from the popular religious mind. The Church has surrendered her once lofty concept of God and has substituted for it one so low, so ignoble, as to be utterly unworthy of thinking, worshipping men. This she has done not deliberately, but little by little and without her knowledge; and her very unawareness only makes her situation all the more tragic."

The Knowledge of the Holy, A.W. Tozer, 1961.

Tozer believed that because Christians had “shrunk” God in their minds, they were suffering from several “lesser evils”:

The “Program” over Presence: He lamented that worship had become a “program” (a word he noted was borrowed from the theater) rather than a direct encounter with the Divine (which is incidentally the goal of the Liturgy.)

Lack of Awe: He felt that Christians had become too “chummy” with God, losing the biblical sense of “fear and trembling” or “holy dread.”

Moral Decline: He argued that you cannot keep your moral life straight if your idea of God is crooked. If God is “ignoble” (small, weak, or easily managed), then your lifestyle will eventually reflect that same lack of weight.

The altar matters profoundly because it counters this cultural drift, fostering communal humility over individual consumption. In Psalm 50’s economy, worship isn’t a product to be marketed but a sacrifice where “the bones You have broken may rejoice” (v. 8). Without it, services can become inspirational events, effective for initial engagement but lacking the sacramental depth that transforms. I have often found it ironic that many modern churches offer “altar calls” but actually have no altar, leading me to ponder, "what is their altar?”

Saint Gregory of Nyssa reflects: “True worship is the offering of a pure heart, not external pomp,” warning against the false emotionalism that staging breeds—those manufactured highs from lights and music that simulate the Spirit’s fire but ignore the psalm’s compunction. As St. John Cassian observes in his Conferences, “Tears from grace humble the soul; from manipulation, they puff it up,” echoing how consumer worship taps impulses for short-term retention, much like LDS emphasis on “burning in the bosom” as confirmation, which Brigham Young himself described as an emotional witness but cautioned must align with doctrine. Yet, Psalm 50 demands more: “Then You shall be pleased with the sacrifices of righteousness, with burnt offering and whole burnt offering” (v. 19)—a heart laid bare at the altar.

In heeding Psalm 50’s call, what if rediscovering the altar restores the mercy David sought? As Malachi prophesied of a “pure offering” from east to west (1:11), the altar connects us to the apostolic cloud of witnesses, inviting a worship that heals the wounds of individualism. Ezra Taft Benson, an LDS leader, once said, “Pride is the great stumbling block to Zion,” a sentiment that parallels the humility the altar demands—far from consumer competition, it’s where we find the God who “will not despise” our contrite hearts.

Sermons, TED Talks, and the Focus of Worship

As Psalm 50 unfolds its plea—“Do not cast me away from Your presence, and do not take Your Holy Spirit from me” (v. 11)—it lays bare the soul’s deepest need: not eloquent words or stirring oratory, but the abiding presence of God Himself. This isn’t a call for intellectual stimulation or motivational uplift; it’s a cry for divine communion, where the heart, stripped of pretense, finds renewal in the Spirit’s quiet work. In this vein, the sermon—or homily—serves not as the pinnacle of worship but as a humble servant, preparing the soil of the soul for the seeds of grace. Yet, when we contrast the TED-talk style of many pastors’ sermons with the integrated Orthodox homily, Psalm 50’s insistence on authenticity over showmanship comes into sharp relief, revealing how cultural forces have reshaped preaching, often at the expense of sacrificial depth.

In American Protestant traditions, the sermon often stands as the centerpiece, a dynamic exposition of Scripture that feels alive, personal, and immediately applicable—like a well-crafted TED Talk designed to inspire action and transformation. There’s profound value here: the passion for God’s Word, the emphasis on practical faith, the way it equips believers to live out the Gospel in daily life. As 2 Timothy 4:2 urges, “Preach the word; be ready in season and out of season; reprove, rebuke, exhort, with great patience and instruction.” Preachers excel at this, drawing from the Reformation’s pulpit-centric legacy to make theology accessible. Francis Chan, a compelling Evangelical voice, captures this when he says, “Worship isn’t a show; it’s surrender,” a reminder that even in motivational formats, the goal is yielding to Christ. Yet, in a consumer age, these sermons can veer toward entertainment, with storytelling, humor, and emotional arcs tailored to hold attention, much like self-help seminars. This risks echoing Psalm 50’s warning: “You thought that I was altogether like you; but I will rebuke you” (v. 21) in mistaking human eloquence for divine encounter.

The origins of this style deepen the contrast. Rooted in revivalism’s emotional fervor, think of Billy Graham’s crusades, where sermons were crafted to convict crowds amid swelling choirs. The modern Evangelical sermon evolved under the sway of consumerism. Leaders like Rick Warren advocated for messages that “meet felt needs,” as he writes in *The Purpose-Driven Church*: “People aren’t looking for a friendly church; they’re looking for friends... We must show them that Christianity is relevant to their everyday lives.” In a society where churches compete with podcasts and TED conferences for mindshare, this approach hooks attendees through relatable, feel-good content, tapping into impulses for self-improvement and inspiration. It works short-term, fostering growth and retention, but as St. Theophan the Recluse observes, “Do not trust sensible warmth; seek the Spirit’s quiet fruit”—manufactured emotional highs coming with polished delivery can simulate conviction without the psalm’s contrition, leaving souls chasing affirmation rather than repentance.

Apostolic homilies, by contrast, are briefer, woven seamlessly into the liturgy, serving not as the main event but as a bridge to the Eucharist. Saint John Chrysostom, the “golden-mouthed” preacher of antiquity, modeled this: His homilies expounded Scripture to illuminate the Mysteries at the altar, preparing hearts for communion. “The homily,” he taught, “prepares the heart for the sacred oblation, that we might partake worthily.” Here, preaching bows to the greater sacrifice, aligning with Psalm 50’s vision: “Then I will teach transgressors Your ways, and sinners shall be converted to You” (v. 13), not through rhetorical flair, but through the Spirit’s convicting power. In Orthodoxy, the focus remains on the altar, where words give way to the Word made flesh (John 1:14), countering individualism with communal humility. Even LDS leaders like Ezra Taft Benson warned against “emotionalism without substance,” noting that true testimony comes from the Spirit’s still, small voice, not orchestrated highs—a parallel caution against sermons that prioritize engagement over essence.

In the light of Psalm 50, TED-style sermons may edify the mind and stir the emotions, but they risk serving the self rather than the Savior. True worship, as Romans 12:1 declares, is our “reasonable service”—a living sacrifice at the altar, where the homily humbly points us to Christ’s mercy. What if we let David’s plea reshape our listening: Does this word foster a clean heart, or merely a fleeting thrill? The patristic wisdom calls us back: Surrender the stage for the sacred, and find the Spirit who renews.

Conclusion

As we journey through Psalm 50’s shadowed valleys—“Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean; wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow” (v. 7)—we emerge with a vision of worship not as polished performance but as raw, redemptive offering. This psalm, etched in the fire of David’s repentance, dismantles our facades, revealing that God’s mercy meets us not in our strengths but in our brokenness. Summing up our reflections: The stage, born of revivalist zeal and consumer competition, draws with emotional allure and individualistic appeal, simulating the Spirit’s fire through lights, music, and motivational words—effective for the moment, but often fading like mist. The altar, rooted in apostolic antiquity, demands our contrite hearts, redirecting praise upward in vigilant sacrifice, where homilies serve the Eucharist’s mystery. In this contrast, Psalm 50 stands as sentinel: “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit” (v. 17)—not spectacles for our ego, but surrender to His sovereignty.

The broader implications strike at our modern malaise: In an age of individualism, where faith is commodified and emotions easily manipulated, Orthodox worship heals our souls by reclaiming the communal, the sacramental—the path to theosis, union with God. Saint Basil the Great reminds us: “The altar is the place where heaven and earth meet, where we offer ourselves to the One who offered all.” For those wandering from LDS testimonies or Evangelical highs, this is no distant echo but a living invitation: The altar calls you home, to the mercy David sought, where false fires yield to the true Light. As Saint Gregory Palamas affirms, “The Holy Spirit descends not on the proud, but on the humble who cry out for cleansing.”

Dear readers, please heed Psalm 50’s final triumph: “O Lord, open my lips, and my mouth shall show forth Your praise” (v. 15). Step beyond the stage’s glow, or the pulpit's proclamations, into the altar’s shadow—visit a Divine Liturgy, stand in its ancient rhythm, and offer your heart. In that sacred space, you will not find fleeting emotion, but eternal embrace: Christ Himself, who turns our ashes into Alleluias. For in His mercy, the broken are made whole, and worship becomes not what we consume, but the song of souls set free.

A note and Recommendations

For those deeply immersed and attached to the emotionalism evoked in modern American protestant worship, the orthodox liturgy may feel flat, maybe you feel like you are struggling to connect with God.

If you’re coming from a background that emphasizes large emotional reactions as divine encounters, and you're dipping your toes into the Divine Liturgy and feeling that emotional flatness or disconnection, you’re not alone. The vibrant highs of contemporary worship songs, the personal testimonies, the sense of immediate inspiration— the lack of those can make the Orthodox service seem staid, even distant. But here’s the gentle truth: True connection with God often blooms not in fleeting emotions, but in the quiet soil of humility, mystery, and participation. As Saint Theophan the Recluse teaches, “Prayer does not consist in standing and bowing your body or sighing from the heart, but in a sober and undistracted attention to God.” Let’s unpack some advice, drawn from the Fathers and my own reflections, to help bridge that gap without dismissing your background.

First, prepare your heart like soil for planting. Orthodox liturgy isn’t a performance to consume; it’s a heavenly banquet to enter. Before attending, spend time in quiet prayer or reading the Psalms—Psalm 50 (LXX) is a gem: “Create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me” (v. 10). This shifts your focus from seeking an emotional rush to offering repentance. Saint John of Kronstadt advises: “Before going to church, prepare yourself by reading the prayers of the Hours or the Canon, that your mind may be attuned to the divine harmony.” If the service feels flat, it might be because we’re arriving as spectators rather than pilgrims. Try fasting lightly beforehand, as the Fathers prescribe—it heightens spiritual sensitivity without the crutch of manufactured fervor.

Second, embrace the standing and the stillness as acts of love. American Christians often sit comfortably, absorbing a sermon like a TED talk, but in Orthodoxy, we stand much of the time, echoing Saint Basil the Great: “We pray standing... to remind ourselves that we are citizens of heaven.” This “discomfort” isn’t masochism; it’s vigilance, training the body to submit to the spirit. If emotions don’t surge, lean into the icons—they’re windows to the saints’ communion with God. Lift up your heart and gaze at Christ Pantocrator and whisper, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” Saint Symeon the New Theologian reminds us: “The grace of the Holy Spirit comes not with noise, but in stillness and humility.” That “flatness” might be the space where God whispers, free from the emotional manipulation of lights and music that seek to simulate the Spirit but often fade.

Third, participate actively, even if it feels foreign at first. Chant the responses if you can—”Lord, have mercy” isn’t rote; it’s the heartbeat of repentance. If you are not Orthodox, you cannot partake of the Eucharist but go with the rest of the congregation. Approach the Priest to receive a blessing with awe and understanding that you are approaching the Lord's servant at the altar. If connection eludes you, remember: Liturgy is objective worship, joining heaven’s chorus (Revelation 4-5); it is not dependent on your feelings. Saint Seraphim of Sarov said, “Acquire the Spirit of peace, and thousands around you will be saved”—peace, not excitement, is the fruit. Over time, as I did, you’ll find emotions follow obedience, not lead it. More than anything, take the opportunity to close your eyes and listen for that still small voice.

Finally, be patient with the transition. Orthodoxy isn’t about instant highs; it’s about the pilgrimage towards theosis, gradual union with God. Talk to a priest—they’re shepherds, not performers. Read *The Way of a Pilgrim* for insights on ceaseless prayer amid “flatness.” As Saint John Chrysostom encourages: “Do not be saddened if you do not feel immediate sweetness; persevere, and grace will come.” Your struggle is a holy one—it’s the Cross refining your worship from self-centered to Christ-centered.

In the end, dear friend, if the liturgy seems to you to be emotionally barren, it might be pruning away what’s artificial to reveal the True Vine (John 15:1). Persist, and you’ll discover a connection deeper than any stage could offer: the quiet, eternal embrace of the Triune God.

Psalm 50 in the Orthodox Study Bible (Septuagint) is Psalm 51 in the Protestant Bible. The numbering is different in each. Not because the OSB is missing a psalm, but because in the Septuagint (created in the 3rd century B.C.) Psalms 9 & 10 are combined into one that is just Psalm 9. In the LXX (Septuagint), some psalms are "combined,” while the Masoretic text Psalm 147 is split into Psalms 146 & 147. The LXX actually has a psalm 151, while the protestant bible ends at Psalm 150. This is a short psalm titled "This Psalm is a genuine one of David." It describes David's victory over Goliath. While it is not in Protestant Bibles, it was found among the Dead Sea Scrolls in Hebrew, proving its ancient roots.

Either in the LDS sense of raising the “priesthood” leaders above the ward members, or in the literal sense of a stage with a band and a preacher. In each case, people are the focus of "worship” services as they are raised up, and the congregation’s attention is oriented towards them.

I'm being somewhat tongue-in-cheek here, fully aware that a primary criticism of modern evangelical/protestant worship, mostly coming from those professing an apostolic faith, is that it is not worship at all, but instead a concert and a TED Talk. Engineered specifically to reflect and attract those living in a modern secular culture.

Elevation Emotion is described in several ways:

Warmth: A literal sensation of “caloric” heat or a glowing feeling in the chest.

Peace and Serenity: A deep sense of “correctness” or “at-home-ness” that settles the mind.

Expansion: A feeling that one’s soul is “enlarging” or becoming more open.

Clarity: A sudden “stroke of pure intelligence” where complex things suddenly make sense.

Scientific Explanation: Elevation Emotion

Psychologists use the term “Elevation” to describe a specific positive emotion triggered by witnessing acts of moral beauty, virtue, or deep spiritual meaning.

The Feeling: It is characterized by a warm, tingling, or “swelling” sensation in the chest and a feeling of being “uplifted.”

The Biology: Research suggests it is linked to the release of oxytocin (the “bonding hormone”) and the activation of the vagus nerve.

The Effect: It often motivates people to become better versions of themselves, which aligns with why many religious people interpret it as a divine call to action.

https://cdn.bookey.app/files/pdf/book/en/the-purpose-driven-church.pdf

Page 3, About this book notes; “this seminal book offers a blueprint for building a spiritually vigorous, engaging, and community-oriented church"

While most pastors and worship leaders would say they are simply “creating an atmosphere for the Holy Spirit,” many of the techniques used are identical to those used by concert promoters and stage producers to trigger specific psychological responses. Here are the primary indications and techniques that suggest these experiences are, at least in part, carefully engineered:

Acoustic and Musical “Triggers.”

Modern worship music often relies on specific songwriting structures designed to build emotional tension and release.

The “Crescendo” and “The Octave Jump”: Songs often start quietly and build toward a loud, high-energy bridge. Worship leaders frequently “jump the octave” (singing the same melody but much higher) at the emotional peak of a song, which serves as a psychological cue for the audience to increase their own intensity.

Repetitive Bridges: Repeating a simple phrase like “You are worthy” for several minutes can induce a mild trance state or “flow state.” This repetition lowers cognitive resistance and makes the listener more susceptible to the lyrics’ message.

The “Vamp”: When a pastor begins an altar call, a keyboardist or guitarist will often play a soft, repetitive chord progression in the background. Psychologically, this “pads” the silence, reduces the awkwardness of the moment, and uses music to “carry” the weight of the speaker’s emotional appeal.

Environmental Lighting and Stagecraft

Mega-churches often spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on “production.”

Darkened Auditoriums: By dimming the “house lights” and focusing bright lights on the stage, leaders create a sense of anonymity. People are more likely to cry, raise their hands, or dance when they feel they aren’t being watched by their neighbors.

Color Psychology: Blue and purple lighting are often used during “introspective” or “prayerful” moments to induce calm, while warm ambers and bright whites are saved for “celebratory” moments of high energy.

“The Wave” Effect (Social Contagion)

Sociologists have noted that emotional religious experiences often function like a “wave” at a stadium.

Mirroring: Humans naturally mirror the emotions of those around them. If a worship leader is weeping or visibly “shaking” on stage, it provides a social “permission slip” for the congregation to do the same.

Expectation: When a service is branded as a “Night of Power” or a “Revival,” participants arrive with a high level of anticipation. This psychological “priming” makes it much more likely that they will interpret any physical sensation (a chill, a racing heart) as a divine encounter.

The “Shepherding” vs. “Manipulation” Debate

The distinction between “leading” and “manipulating” is a major point of debate among church leaders themselves.

The Case for “Shepherding”: Many leaders argue that since God created human emotions, it is “good and right” to use music and lighting to help people engage their hearts. They see it as “priming the pump” for a genuine spiritual connection.

The Case for “Manipulation”: Critics (and some former worship leaders) argue that if you can produce the exact same “burning in the bosom” or “move of the spirit” at a Coldplay concert or a secular motivational seminar using the same lighting and music tricks, then the experience is biological, not necessarily theological or spiritual.

Indicators to Look For:

If you are trying to determine if a service is being “manufactured,” look for these “tells”:

The Musical “Nudge”: Does the music swell precisely when the pastor makes a specific emotional point or asks for money/commitment?

Formulaic Structure: Does every service follow the exact same “emotional arc” (2 fast songs, 2 slow songs, emotional story, altar call)?

Coerced Response: Does the leader use “command” language? (e.g., “Nobody leave,” “I feel like someone here is resisting the Spirit,” “Don’t hold back.”)

while the evolution of American worship away from it reflects cultural shifts that, though well-intentioned, risk diluting Psalm 50’s call for inner transformation.

The Knowledge of the Holy, published in 1961, A.W. Tozer.