The Communion of Saints: A Biblical Defense of Intercessory Prayer

A case for intercessory prayer

I have recently been in discussion with a friend who has an issue with intercessory prayer. This friend is relatively adamant that this is wrong and has stated to me that they will not change their mind because they “believe in the bible.” This article is not meant to convince them (because they’ll never read it), but to help others understand the context of the practice and explore the support for this practice, as well as to put the arguments against it into proper context. I hope to base most of this discussion on the Bible since american protestant christians adhere firmly to the (demonstrably false) Reformation doctrine of Sola Scriptura.

The doctrine of sola scriptura is a foundational principle for many Christians, emphasizing that the Bible is the final and sufficient authority for all matters of faith and practice. When examining the Orthodox practice of asking saints to pray for us, it is important to approach the topic from this framework, demonstrating that this tradition is not only permissible but also a natural extension of core biblical truths.

This defense rests on three fundamental pillars that we’ll explore in detail after the paywall below:

The ongoing, active life of the saints in Christ;

The scriptural pattern of intercessory prayer within the Body of Christ, and

The preservation of Christ’s unique role as the sole mediator of salvation.

We’ll also look at archeological evidence for the practice (praxis) of invoking the saints.

Who are the Saints?

My chatechist explains it using a sports analogy. In many sports, athletes are recognized in the Hall of Fame for their outstanding achievements. For us, the Saints are the “hall of fame’ers” of Christianity. Those who in this life achieved Theosis or a very high level of spiritual progression and holiness, and as a result, after their repose, their souls are with Christ.

1 The Saints are Consciously Alive and Active in Christ

A common objection to asking saints for prayer is the assumption that the dead are unconscious or that death severs their connection to the living. However, Scripture presents a different reality. The saints who have departed this life are not unconscious or removed from the Body of Christ; they are more alive than ever, in the immediate presence of God.

Luke 20:37-38: Jesus Himself declares, “He is not the God of the dead, but of the living, for all live to him.” This statement affirms that for God, there is no state of unconsciousness for those who have died in the faith. They are fully alive. This is why in the Orthodox church, we do not say that people are dead. We might say they are asleep or that they have reposed, but that is different from death.

Philippians 1:21-23: The Apostle Paul expresses his desire to depart and “be with Christ, for that is far better.” For background, in the context of this scripture, Paul is in prison and facing the possibility of death. He states that for him, “to live is Christ, and to die is gain.” (Ph 1:21) In other words, his life’s purpose is to serve Christ, but death would be a direct benefit because it would mean being in the presence of Christ. He expresses a strong desire to “depart and be with Christ,” because he believes that is “far better.”

The Greek word for “depart” here (analysai) can also mean “to un-moor” a ship or “to break camp,” suggesting a journey or a move from one place to another. This language indicates a conscious transition, not a period of rest or unconsciousness.

The scripture is not about him settling down or being at peace facing death in his current situation, but about his active longing for the moment he will be fully united with Christ, which he clearly views as a conscious and immediate state. He does not anticipate an unconscious slumber, but a conscious, immediate union with Christ.

Revelation 6:9: “When he opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain because of the word of God and the testimony they had maintained. They called out in a loud voice, “How long, Sovereign Lord, holy and true, until you judge the inhabitants of the earth and avenge our blood?” Then each of them was given a white robe, and they were told to wait a little longer, until the full number of their fellow servants, their brothers and sisters, were killed just as they had been. This is a direct, visual depiction of the martyred saints being fully conscious, actively engaged, residing in the presence of God, and asking God for justice.

Hebrews 12:1: “Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses, let us throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles. And let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us.” The Greek word for “witnesses” is martyron, the same root for “martyrs.” These witnesses are not passive spectators; they are active testifiers in the great race of faith, cheering us on and participating in our spiritual journey. Their victory is our encouragement, and their union with God makes their prayers potent.

The biblical witness is clear: death is a transition to a more perfect life, not an end to spiritual activity. For the Christian, to be “absent from the body” is to be “at home with the Lord” (2 Corinthians 5:8-9). “We are confident, I say, and would prefer to be away from the body and at home with the Lord. So we make it our goal to please him, whether we are at home in the body or away from it.”

2 Intercessory Prayer is a Scriptural Pattern for All Believers

Almost all evangelical Christians readily embrace the idea of asking a friend or family member to pray for them. This is an act of intercession, a form of mediation. The practice of asking the saints for prayer is simply an extension of this biblically approved principle, based on the understanding that the saints in heaven are just as much, if not more, a part of the Body of Christ than we are.

1 Timothy 2:1: Paul explicitly commands, “I urge that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and thanksgivings be made for all people.” Intercession is a duty for all believers.

James 5:16: “… The prayer of a righteous person is powerful as effective.” This verse emphasizes the effectiveness of the prayers of those who are righteous. Who could be more righteous than those who are fully perfected in Christ, standing in His immediate presence?

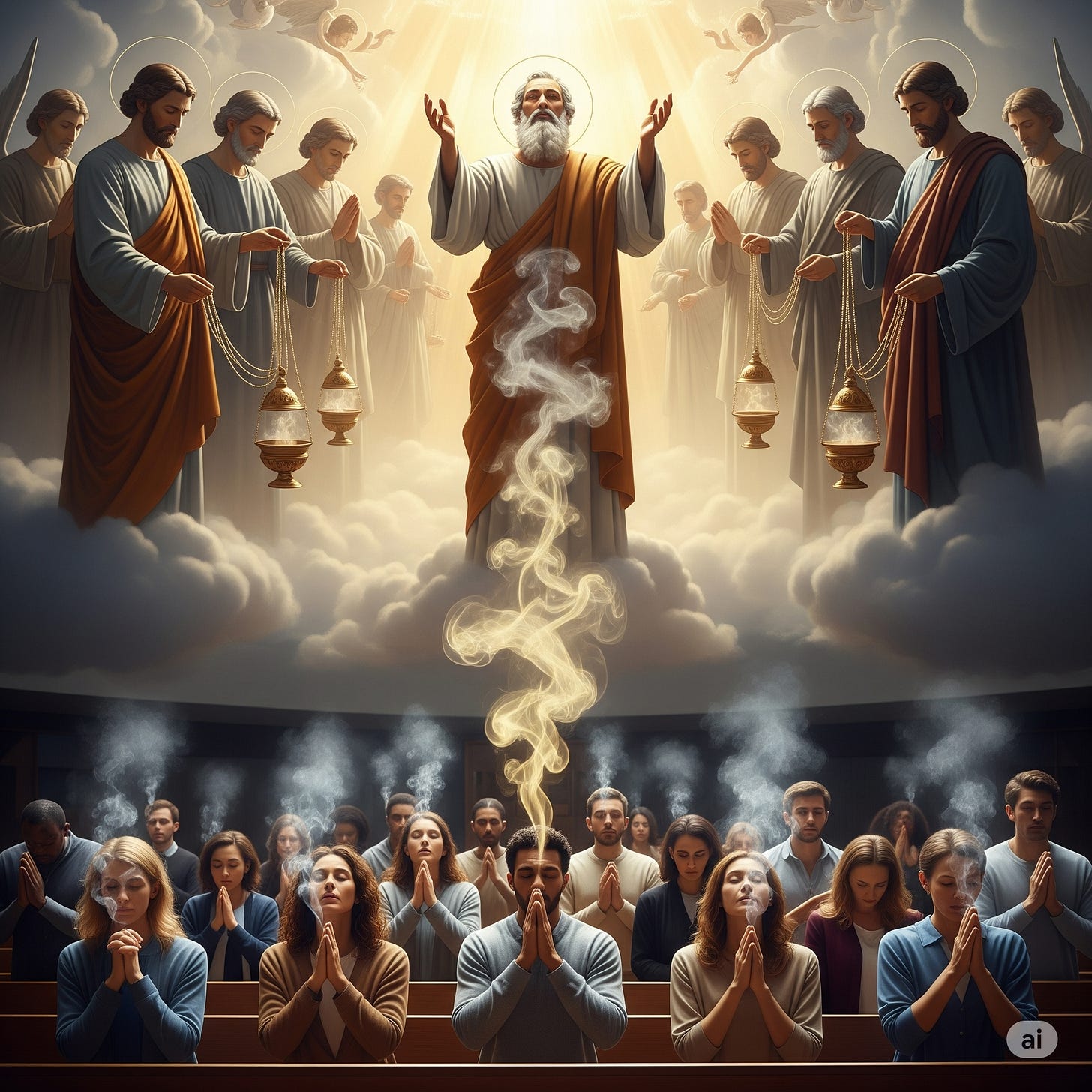

Revelation 5:8: This is perhaps the most direct scriptural evidence. The twenty-four elders in heaven, who represent the perfected saints of the Old and New Testaments, are seen holding “golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints.” This passage shows that the prayers of believers on earth are offered to God through the saints in heaven. It is a heavenly liturgy in which the saints play a clear and active role.

Revelation 5:8 and Revelation 8:3-4. In Revelation 5:8, the Apostle John sees the “four living creatures and the twenty-four elders” (The twenty-four elders in heaven represent the perfected saints of the Old and New Testaments), and they are holding “golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints.” It is clear that God is not simply receiving the prayers of believers on earth; they are being actively gathered and presented to Him by the saints in heaven. This is a powerful picture that connects heavenly worship with earthly prayer. In the Old Testament, the burning of incense on the altar was a symbol of prayer ascending to God (Psalm 141:2)1. The elders—who represent the perfected saints of both the Old and New Testaments—are acting as heavenly priests, offering the prayers of the Church to God. A similar image is repeated in Revelation 8:3-4, “Another angel, who had a golden censer, came and stood at the altar. He was given much incense to offer, with the prayers of all God’s people, on the golden altar in front of the throne.” The smoke of the incense is explicitly identified as the prayers. “The smoke of the incense, together with the prayers of God’s people, went up before God from the angel’s hand.” This reinforces the idea that the prayers of believers on earth are not private, solitary acts but are part of a heavenly liturgy of the body of Christ. The saints and angels in heaven participate in this liturgy, presenting our petitions to God. This illustrates a very direct biblical argument that shows that those who have “died” in Christ are still active, conscious, and involved in the prayer life of the Church.

The saints’ intercession is not an act of usurpation but one of cooperation. They do not replace Christ’s mediatorship; they participate in the great work of prayer that He has entrusted to His Body.

3 The Distinction of Christ’s Mediation

The most common objections to intercessory prayer come from Old Testament prohibitions against necromancy (which we’ll examine below) and 1 Timothy 2:5: “For there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus.” This verse is rightly understood to mean that Christ is the sole atoning, salvific mediator. He alone is God and man, able to bridge the infinite gap created by sin and reconcile humanity to the Father through His sacrifice.

We Orthodox fully affirm this. When we ask a saint to pray for us, we are not asking them to atone for our sins, save us, or mediate a new covenant. We are asking them to do what we ask our friends on earth to do: to lift our needs before God.

For Example, consider the role of Moses in the Old Testament. He frequently acted as an intercessor for Israel before God, and God often responded to his prayer (Exodus 32:11-14; Numbers 11:2). Was Moses replacing God? No. He was acting as a righteous man whose prayer had great power. The saints are a continuation of this biblical tradition, only now they are perfected in Christ.

The prayer of the saints is not an alternative to praying directly to God, but a powerful complement to it. It is a recognition that we are not solitary individuals but part of the living Body of Christ, a family, if you will, that spans heaven and earth.

Addressing the Prohibition Against Necromancy

Key scriptural objections often raised by Evangelicals are the biblical prohibitions against “speaking to the dead” found in passages like Deuteronomy 18:11 and Isaiah 8:19. A careful exegesis reveals that these verses are prohibitions against pagan practices of Necromancy, not against communal prayer within the Body of Christ.

Deuteronomy 18:10-12: “Let no one be found among you who sacrifices their son or daughter in the fire, who practices divination or sorcery, interprets omens, engages in witchcraft, 11 or casts spells, or who is a medium or spiritist or who consults the dead. 12 Anyone who does these things is detestable to the Lord; because of these same detestable practices, the Lord your God will drive out those nations before you.” Many Evangelicals object to intercessory prayer based on the assumptions that the Saints are dead and that this injunction applies. The context of this passage is a condemnation of pagan occult practices that were prevalent among the Canaanites. These forbidden acts—such as being a medium, a necromancer, or one who consults spirits— were not attempts to commune with God, but instead attempts to gain secret knowledge or divine guidance by channeling or conjuring the spirits of the deceased (this injunction is before Christ harrowed Hell so these are indeed the spirits of the dead.) This practice was a direct replacement for seeking God’s will through His appointed prophets and His law. This is much like the sin of Adam, who attempted to get the knowledge to become like God on his own, without God.

Isaiah 8:19: “When someone tells you to consult mediums and spiritists, who whisper and mutter, should not a people inquire of their God? Why consult the dead on behalf of the living?” The prophet Isaiah warns against turning to mediums and necromancers who whisper and mutter instead of seeking “the law and the testimony” of God. The concern here is about divination and sorcery, a way of seeking forbidden information that bypasses God’s authority and wisdom.

The Orthodox practice of asking for the saints’ prayers is fundamentally different from necromancy.

It is not about channeling or conjuring spirits.

It is not about seeking illicit, forbidden, hidden, or future information from a source other than or outside of God.

It is a humble request for a fellow, living member of the Body of Christ, to pray to God on our behalf. We believe the saints are fully alive in Christ’s presence and are aware of our needs.

The practice is an act of communal prayer and veneration, not an act of divination. We venerate the saints for their heroic faith and because they are glorified by God, but our worship (latreia) is reserved for God alone.

Disambiguating Terms and Concepts

There are some things, definitions, and distinctions that I wish to point out as we proceed. In the West, particularly in modern America, the distinction between worship, communication, and veneration has been lost or forgotten in a religious context, leading to mistaken thinking that sometimes causes protestants to accuse us of idolatry.

Veneration comes from the Latin venerari, which means “to revere.”

Within the Orthodox church, there is a clear theological distinction made between worship and veneration that is made using Greek terms.

Worship (Latria): This is the highest form of adoration and religious service, reserved for God alone. It is a recognition of God as the Creator, the ultimate authority, and the source of all being. To offer latria to anyone or anything else is considered idolatry.

Veneration (Dulia): This is a profound respect and honor shown to created beings who have a special relationship with God. It is a recognition of their holiness and their place as “friends of God.” The Orthodox Church also has a special term for the honor given to the Virgin Mary, hyperdulia, which is a higher form of veneration but is still not worship.

The distinction is crucial. When a person venerates a saint, an icon, or a relic, they are not treating that person or object as God. Instead, they are honoring the holiness of the person or the spiritual reality they represent, and asking them to pray to God on their behalf. The honor given to the image or person “passes to the prototype,” meaning the respect is ultimately directed toward God, who made them worthy of such honor in the first place.

This is analogous to how one might respect and honor a secular hero. You might praise them, put their photo on a wall, and celebrate their deeds, but you would not worship them as a god.

Prayer is a form of communication to ask for something. Prayer itself is not Worship.

The word “pray” comes from the Latin precari, meaning “to entreat, beg, or implore.” In its original and most common usage in Early Modern English, it was a way of expressing a sincere request or polite entreaty to another person, not just to a deity. It was a formal and respectful way of saying “I beg you,” or “I ask you.” This meaning is why you often see phrases like “I pray you” or “pray thee” in older texts and plays. It was a common linguistic formula for making a courteous request. While it could certainly be directed toward God, its use among people was equally, if not more, prevalent.

Shakespeare’s works are filled with examples of “pray” used in this sense of a polite request or entreaty. In Shakespeare’s time, “pray” was a versatile and common word used to make a polite or earnest request to anyone, high or low, in both formal and informal contexts.

“Pray you, sit.”

This is one of the most common usages. It’s a simple, formal way of saying “Please, sit down.” It’s a direct request to another person.

“Pray, do not mock me.”

From A Midsummer Night’s Dream, this line is a plea from Hermia to Lysander. She is begging him to stop, not praying in a religious sense. It’s a direct, emotional entreaty.

“I pray you, father, do not look with such a bitter eye upon my poor innocence.”

In King Lear, this is Cordelia’s direct appeal to her father. She is not praying to God but earnestly asking her father to reconsider his harsh judgment.

Worship is neither of the above, although we often confuse these concepts in modern everyday life. The English word Worship initially meant to ascribe value or worth to something (worth+ship) and was typically used in a secular context (i.e., a medieval Lord might be addressed as “Your Worship” as a title to ascribe worth, dignity, and honor to a particular individual). Later on, the word became almost exclusively associated with the honor and reverence given to God (or another divine being) when English translations of the bible used the word to translate Hebrew and Greek words that mean to bow down, show homage, and to serve God.

Shachah (שָׁחָה): This is the most common Hebrew word translated as worship. Its literal meaning is to prostrate oneself or to bow down. This act can be done as a sign of reverence to God (Genesis 24:26), but it is also used to show respect to other people, such as Abraham bowing before the Hittites (Genesis 23:7) or Jacob bowing before Esau (Genesis 33:3). The context determines if the act is religious worship or secular honor.

Abad (עָבַד): This word means to serve or to labor. While it can describe manual labor, it is also used to describe serving God (Deuteronomy 6:13). It points to worship as a full-life service and obedience, not just a physical posture.

Proskuneo (προσκυνέω): This word is the Greek equivalent of shachah. It literally means “to kiss toward” and refers to bowing down or prostrating oneself in homage. It is the most common Greek word for worship, and it is used for both the adoration of God (John 4:24) and the homage paid to a human king (Matthew 2:2).

Latreuo (λατρεύω): This is the Greek equivalent of abad and means to render religious service. This term is always used in the Bible to refer exclusively to the worship owed to God alone. Jesus uses this word when he tells Satan, “You shall worship the Lord your God, and Him only shall you serve (latreuo)” (Matthew 4:10).

Now that we have some concepts disambiguated, we can see that the biblical prohibition against necromancy is about avoiding occult practices, not about forbidding the spiritual communication between living members of Christ’s one, undivided Body.

Evidence from Patristic Sources

Even outside of the biblical text, the practice of intercessory prayer to the saints is found in the earliest Christian writings, showing that this was not a later invention but a practice established soon after the apostolic era. The practice of asking for the intercessory prayers of the saints is a continuous tradition that extends back to the earliest centuries of the Church, as evidenced by the writings of the Church Fathers.

The video below also review the evidence from early christian sources.

Even outside of the biblical text, the practice of intercessory prayer to the saints is found in the earliest Christian writings, showing that this was not a later invention but a practice established soon after the apostolic era.

Origen of Alexandria (c. 185-254 AD)

Origen’s connection to the apostles is through a chain of teachers. He was the disciple of Clement of Alexandria, who, in turn, was the disciple of Pantaenus. According to the historian Eusebius of Caesarea (Ecclesiastical History, Book 5, Chapter 10), Pantaenus traveled to India, where he found a copy of the Gospel of Matthew that had been left there by the Apostle Bartholomew. This places Origen within the established line of apostolic teaching.

Origen wrote about the active role of the departed saints in the prayer life of the Church. In his work, On Prayer, he argues that the righteous who have passed away are still praying for those on earth.

“The High Priest prays with those who pray sincerely... But not only the High Priest, but also the angels... as also the souls of the saints who have already fallen asleep.“ (On Prayer, Book XI)

Lee’s Aside: Note that he uses the term fallen asleep, the same way that we refer to those who have “passed on” in the Orthodox church today.

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-c. 215 AD)

Clement claims to have sat at the feet of “blessed and truly remarkable men” who preserved the “true tradition of the blessed doctrine, directly from the holy apostles, Peter and James and John, and Paul.”

Clement speaks of the communion between the faithful on earth and those in heaven, describing how they all pray together.

“In this way is he [the true Christian] always pure for prayer. He also prays in the society of angels, as being already of angelic rank, and he is never out of their holy keeping; and though he pray alone, he has the choir of the saints standing with him [in prayer].“ (Stromata, 7:12)

Saint Cyprian of Carthage (c. 200-258 AD)

As a convert and a bishop in North Africa, Cyprian’s writings reflect the practices and beliefs of the Church at the time.

Living in an age of intense persecution, Cyprian wrote extensively about the martyrs and actively encouraged his flock to ask them for their prayers once they had entered heaven. In a letter to the persecuted Christians in prison, he wrote:

“And if any of you should go first... do not forget to pray for your friends.” (Letter to the Martyrs and Confessors)

He also told another group of confessors that when they finally passed, their intercession would be even more effective.

“Let us remember one another in concord and unanimity. Let us on both sides [of death] always pray for one another. Let us relieve burdens and afflictions by mutual love, that if one of us, by the swiftness of divine condescension, shall go hence first, our love may continue in the presence of the Lord, and our prayers for our brethren and sisters not cease in the presence of the Father’s mercy.“ (Letters, 56:5)

Archaeological Evidence

I can hear in the back of my mind objections from uneducated protestants and Mormons. “Did early Christians actually engage in this, or is this some later form of corruption post-Nicaea (their favorite boogeyman.) Since the biblical evidence may not have been enough, let’s look at some archaeological evidence.

Recently discovered archaeological evidence (2022) of the practice of intercessory prayer goes back to the mid-first millennium of Christianity, from the archaeological dig at Bethsaida. (5th or 6th century AD.)

The significant inscription found in the mosaic floor of the ancient basilica (known as the “Church of the Apostles”) at Bethsaida is a Greek dedication.

1. Translation of the Main Inscription (from the Diakonikon/Sacristy)

The inscription is a prayer for intercession for the benefactor of the mosaic work.

Translated Text (Summary):

“...[T]he whole work of paving the diaconicon with mosaic was done by the zeal of Constantine, servant of Christ. Chief of the apostles and holder of the keys of the heavenly (spheres), intercede for him and for his children, George and Theophanos.”

This is a clear intercessory prayer made on behalf of the donor Constantine to Saint Peter.

Donor/Benefactor: “Constantine, servant of Christ” (Note: This is not Constantine the Great, but a wealthy church member).

Apostle Reference: “Chief of the apostles” (κορυφὴ τῶν ἀποστόλων) and “holder of the keys of the heavenly (spheres)” (τῶν οὐρανίων κλειδοῦχος).

Significance:

The titles, particularly the reference to the “keys to heaven,” are a clear and common reference used by Byzantine Christians for Saint Peter.

This discovery strongly supports the identification of the church at Bethsaida with the one described by the 8th-century pilgrim Willibald, which was said to be built over the home of the Apostles Peter and Andrew in Bethsaida.

But but but… the APOSTASY!

“But WAIT!” I hear a great weeping, wailing, and gnashing of teeth as protestants suffer meltdowns, “That’s from the 5th century! The church was already corrupted by that time! The GREAT APOSTASY was already in FULL SWING!”

Ok, too late in history for you, eh? Ok, since the biblical evidence itself didn’t seem to sway you, let’s look at evidence from Archaeology and ancient writings.

Much evidence (that we’ve found) points to the practice becoming archaeologically visible in the 2nd century (the second century is in the 100’s AD) and firmly established by the 3rd and 4th centuries CE.

The Abercius Inscription (2nd Century CE)

Artifact: The epitaph on the tomb of Abercius, Bishop of Hieropolis (in modern Turkey).

Date: The 2nd century CE.

Key Phrase: The inscription, written in the first person by Abercius, concludes with a request to the reader:

“Let every friend who observes this pray for me.”

Significance: This is one of the earliest known physical pleas for prayer by a deceased Christian directed at those who come after him; Asking the living to pray for someone deceased! If such a thing was considered necromancy, why would a bishop ask those of his flock to engage in such a practice? (Maybe b/c it wasn’t considered necromancy and people back then were smart enough to know the difference!)

The Frankfurt Silver Inscription (Amulet)

Date: Between 230 and 270 CE (mid-3rd century).

Context: A tiny silver amulet discovered in a Roman grave near Frankfurt, Germany, making it the oldest Christian artifact north of the Alps.

Petition/Veneration: The Latin inscription on the scroll inside the amulet references Saint Titus, a disciple of the Apostle Paul. While not a direct petition, its use in a devotional context as a protective amulet for the deceased is seen as very early evidence of veneration and an appeal for the saint’s powerful presence.

The inscription goes something like this: “In the name of Saint Titus. Holy, holy, holy!2”

“In the name of Jesus Christ, Son of God! The Lord of the world resists with all his might all setbacks. God grants well-being. This amulet protects the person who surrenders to the will of the Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God. Since before Jesus Christ all knees shall bend: those in heaven, those on earth and those underneath, and every tongue shall confess to Jesus Christ.” (from Philippians 2:10-11)

Roman Catacomb Inscriptions (3rd–4th Centuries CE)

Artifacts: Numerous inscriptions on the tombs of Christians in the catacombs of Rome.

Date: Beginning in the 3rd century CE and becoming widespread in the 4th century. Why only the 3rd-4th centuries? Why so late? Well, this corresponds to the periods of intense persecution of Christians by Roman emperors: Decian (250CE), Valerian (257-260CE), Diocletian (303-311CE). (The 200s are the 3rd century, the 300s are the 4th century.) Roman emperors weren’t rounding up and slaughtering Christians en masse in the first and second centuries - thus no need for petitions and there were no Christian catacombs.

Key Phrases: These inscriptions often contain direct petitions to the deceased to intercede for the living or for the dead’s own repose:

“Pray for your parents, Matronata Matrona.”

“Atticus, sleep in peace, secure in your safety, and pray anxiously for our sins.”

Phrases like Vivas in pace (“May you live in peace”) or Pax tecum (“Peace be with you”) were also common, often interpreted as hopeful prayers for the departed.

The Rylands Papyrus (3rd–4th Century CE)

Artifact: A fragment of papyrus found in Egypt.

Date: Dated to around the mid-3rd to 4th century CE.

Key Phrase: This fragment contains the earliest known prayer to the Virgin Mary, known as the Sub Tuum Praesidium (”Beneath Thy Protection”), which explicitly asks for her intercession (imploring her not to disregard petitions in adversity).

“Mother of God, [listen to] my petitions; do not disregard us in adversity, but rescue us from danger, for you alone are pure, you alone are blessed.”

The phrase “you alone are pure, you alone are blessed” is still used in the Orthodox church today.

The development of intercessory prayer (especially to dead saints and for the dead) in Christianity is generally well supported by both archaeological inscriptions and the writings of Church Fathers (like Tertullian and Origen).

Conclusion

The Orthodox practice of asking the saints for prayer is not an act of idolatry or a denial of Christ’s unique mediation. Rather, it is a profoundly biblical and deeply communal practice that celebrates the reality that the Body of Christ is undivided. It is a humble acknowledgment that we are not alone in our struggles and that we can lean on the prayerful support of those who have already conquered the race of faith and now stand in the whole light of God’s presence.

We are not praying to them as deities, but we are entreating them as living, honored members of our family in Christ.

“May my prayer be set before you like incense; may the lifting up of my hands be like the evening sacrifice.”

This is the Trisagion - or thrice holy, which is an important part of Christian liturgy that you can still hear in use in Orthodox Divine Liturgy today. Each “Holy” is for a member of the Trinity. So, in a way this is evidence from the early 3rd century of the belief in the Trinity. (Shock! Gasp! - You mean Christians believed in the Trinity *before* Nicea? Umm yup. Nicea didn’t invent the Trinity, only formally articulated it.)