Beyond the Break: The Story of the Great Schism of 1054 and Who left Who.

Explore the centuries-long political, theological, and cultural conflicts that shaped Christianity’s most defining divide—and challenge everything you thought you knew about who broke away and why.

I’ve had a few conversations with Roman Catholics about orthodoxy, and the first thing they always repeat is the roman catholic propaganda that the East broke off from the West. It’s so pervasive that when I saw a recent YouTube short with a Catholic Bishop repeating the same nonsense to his parishioners, I decided to write something about it. This way, the next time someone says that to me, I can hand them this article to reference.

I've written about the split in recent articles, but without examining the specifics of how the split occurred and the events that led up to it.

Beyond the Paywall

Here is a short summary of what's beyond the paywall:

What if everything you thought about the East-West split was upside down?

A dramatic showdown in a cathedral that changed Christian history forever.

The untold political power plays behind a supposedly spiritual divide.

A single controversial phrase that ignited centuries of conflict.

Why the “official” split was only the climax of a much longer story.

Discover which side really walked away first— who left who, and why it still matters today.

Subscribe now to uncover the detailed history and drama behind Christianity’s defining break and learn definitively who left whom.

The Stage - Roman Empire Politics East vs West

We should mention (but I won’t delve too far into) the fact that Rome and Constantinople were essentially rival capitals of a split Roman Empire, with Rome as the head of the Western Empire and Constantinople as the head of the Eastern Empire (also known as Byzantium). The division of the empire began with Diocletian (286 CE), as he felt the Empire had grown too vast for one ruler to govern effectively.

Almost immediately, each half claimed legitimacy as the True Roman Empire and meddled in each other’s affairs. There were times when the Eastern portion of the empire (wealthier and stronger) asserted its supremacy over the Western part of the empire through diplomatic leverage or religious authority. Conversely, the Western Empire, weaker in resources and more vulnerable to invasions, occasionally attempted to assert its primacy as the guardian of Roman traditions and the historic seat of the empire (Rome). As differences deepened, the two halves became more alienated and frequently competed for legitimacy and influence within the broader Roman world.

Nevertheless, both sides continually sought political ascendancy over the Roman heritage, often invoking ancient claims to legitimacy or unity, even as their rivalry contributed to the final separation of Roman civilization into distinct Eastern and Western legacies. There were brief periods where the empire was reunified, but those never lasted beyond the death of the emperor.

The Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE due to internal decline and external invasions, but the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire persisted for nearly a thousand more years until its fall in 1453 at the hands of the muslim Ottoman Turks.

Politics was undoubtedly at play here, and the underlying political tensions of the empire certainly created the environment that led to the schism.

Background of the Great Schism of 1054

The events of 1054 are often highlighted as the breaking point, but the schism was the culmination of centuries of growing theological, political, cultural, and ecclesiastical differences between the Latin West and the Greek East. These tensions did not erupt suddenly but evolved gradually, with roots tracing back to the early Christian era.

Key drivers included:

Theological Disputes: Primarily the filioque, unilaterally added to the Nicene Creed by the Latin Church around the 9th century. This clause stated that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father “and the Son” (or filioque in Latin), which we viewed, and still view, as a heretical alteration that disrupted the Trinity’s balance and was made without an ecumenical council’s approval. The East argued it diminished the Father’s unique role, while the West saw it as a clarification against Arianism.

Papal Authority vs. Conciliarism: The Latins increasingly emphasized the Pope’s supreme authority over the entire Church, based on succession from St. Peter. In contrast, the rest of the church favored a conciliar model, where authority derived from ecumenical councils.1 Until this point in history, all high-level church issues were addressed in this manner. In contrast, “The pope claimed direct jurisdiction over the whole church, East as well as West,” while the East rejected this as overreach (and they have been consistent on this matter). Regarding the Filioque above, the Latin patriarch (i.e., Pope Benedict VIII AD 1012) felt he could unilaterally modify the creed (despite agreement of all patriarchs - including the pope - at the third ecumenical council of Ephesus that according to Canon VII, specifically prohibited the composition or writing of any other creed besides the one defined by the Fathers at Nicaea.) and did so as a demonstration and exercise of his “right” to papal supremacy.

I should note that a previous pope, Leo III (AD 816) had specifically opposed adding the filioque to the Creed and as a demonstration of his commitment to preserving the original text, he had the Creed—without the Filioque clause—engraved in both Latin and Greek on two silver shields (tabulae) and publicly affixed to the doors of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

That Papal supremacy didn’t exist in the first millennium isn’t a matter of disputed history (if you don’t count Roman Catholic apologists on YouTube). The Vatican's “Libreria Editrice Vaticana” released an Encyclical in 2024 that acknowledges that the pope did not have canonical authority over the other patriarchates. The document is titled “Primacy and Synodality in the Ecumenical Dialogues and in the Responses to the Encyclical UT UNUM SINT,” based on writings from Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI.

“The Orthodox–Catholic international dialogue in its document on Synodality and Primacy during the First Millennium, while noting the right of appeal to major sees, points out that “the bishop of Rome did not exercise canonical authority over the churches of the East” (O–C 2016, 19).” - Page 69. “Primacy and Synodality in the Ecumenical Dialogues and in the Responses to the Encyclical UT UNUM SINT.”

Cultural and Political Divides: Linguistic barriers (Latin vs. Greek), differing liturgical practices (e.g., use of leavened vs. unleavened bread in the Eucharist, clerical celibacy), and geopolitical rivalries exacerbated misunderstandings. The rise of the Normans in southern Italy, a Byzantine territory, added friction as they imposed Latin rites on Greek communities. Prejudice, arrogance, and mutual ignorance further fueled the divide, with neither side truly engaging the other’s perspectives.

I would add that the scriptures used by each “side” were, by this time different with the Latin Vulgate diverging from the Septuagint due to St. Jerome’s decision to use the corrupted Masoretic texts (including the anti-christian changes) as a basis for the Latin translation of the old testament over the Septuagint, which was used by the church (and the apostles themselves) from the beginning. Naturally this is going to result in theological differences over time.

By the 11th century, these issues had simmered into open conflict, particularly under the leadership of strong-willed figures on both sides.

Events Leading to the 1054 Incident

The immediate prelude to the schism involved escalating disputes in 1053–1054. Pope Leo IX (r. 1049–1054), a reformer focused on centralizing papal power and combating simony and clerical corruption, sought to assert Rome’s authority amid Norman incursions in Byzantine-controlled southern Italy. In response to Norman attacks on Greek rites, Patriarch Michael I Cerularius of Constantinople (r. 1043–1059) closed Latin churches in Constantinople and encouraged critiques of Western practices, such as the use of unleavened bread.

Pope Leo IX dispatched a delegation to Constantinople in early 1054 to negotiate and address these grievances, as well as to seek Byzantine alliance against the Normans. The delegation was led by Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida, a staunch advocate of papal supremacy known for his tactlessness and narrow-mindedness. Accompanying him were Frederick of Lorraine (future Pope Stephen IX) and Archbishop Peter of Amalfi. Upon arrival, Humbert engaged in heated exchanges, but Cerularius largely ignored the legates, refusing to meet them formally.

Importantly, Pope Leo IX died on April 19, 1054, before the delegation could complete its mission. This technically invalidated their authority, as papal legates’ powers typically ceased with the pope’s death. However, the delegation proceeded, either unaware or undeterred.

The Papal Bull Incident

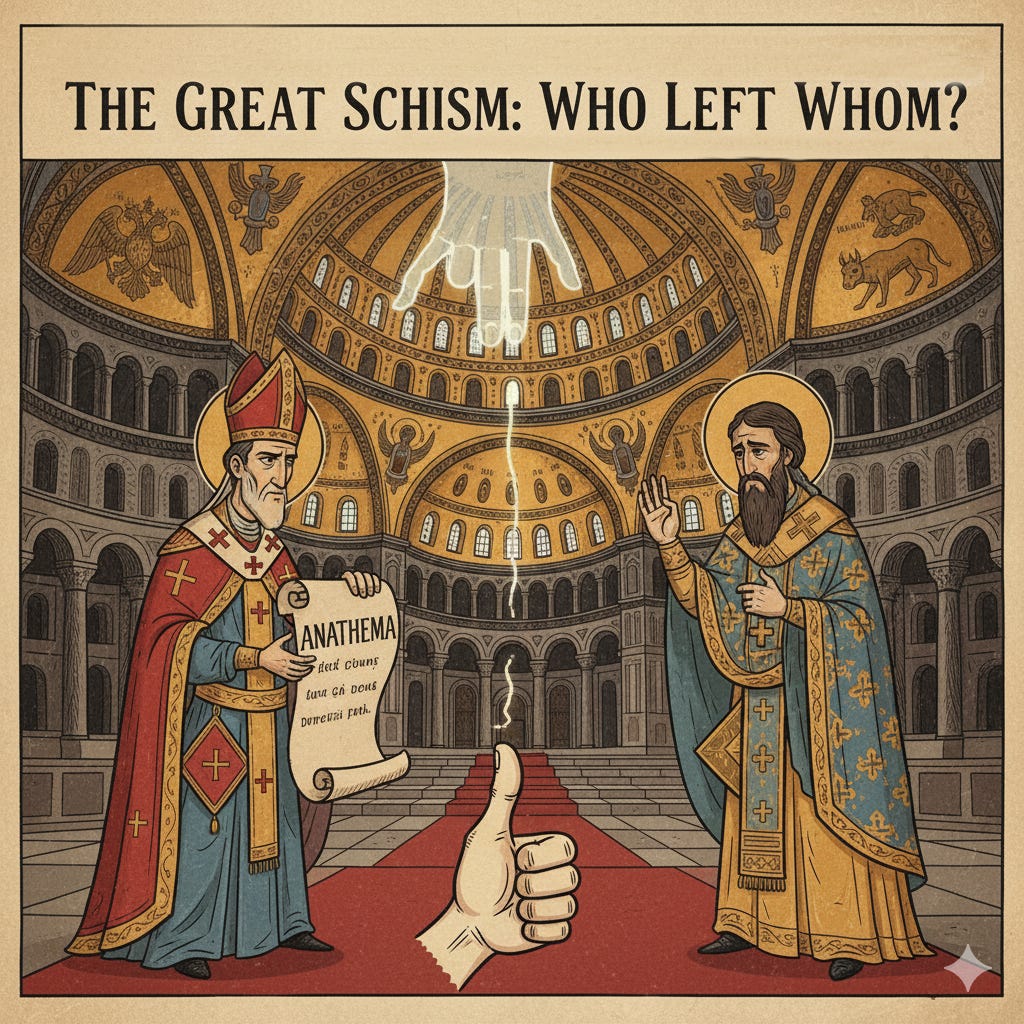

Frustrated by the impasse, on July 16, 1054, during the afternoon liturgy (i.e. Mass for Latin readers) at the Hagia Sophia—the grand cathedral in Constantinople—Cardinal Humbert dramatically interrupted the service. He strode into the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia, right up to the main altar, and placed on it a parchment that declared the Patriarch of Constantinople, Michael Cerularius, to be excommunicated. The bull, issued in the name of the deceased Pope Leo IX, accused Cerularius and his supporters of various heresies and schismatic acts, including simony, rebaptism of Latins, and omission of the filioque (the brazen arrogance and the irony.) Humbert then shook the dust from his feet as he exited, symbolizing rejection.

This act was performed by Cardinal Humbert under the authority of Pope Leo IX, despite the pope’s prior death rendering the bull legally questionable in hindsight. A week later, on July 24, Cerularius convened a synod that excommunicated Humbert and the legates in retaliation, though notably not the entire Western Church or the pope himself.

We can see from this incident that the first blow in this fight was thrown by Roman Catholic emissaries not the Eastern church(s). The east also refrained from excommunicating the west, leaving the door open to reconciliation.

Making Sense?

Hopefully by now you can see which side took their toys and stomped off in a huff and who left who should be relatively clear. However, just in case I’m going to present what I call the “Kindergarten version” as an illustration.

The Kindergarten Version

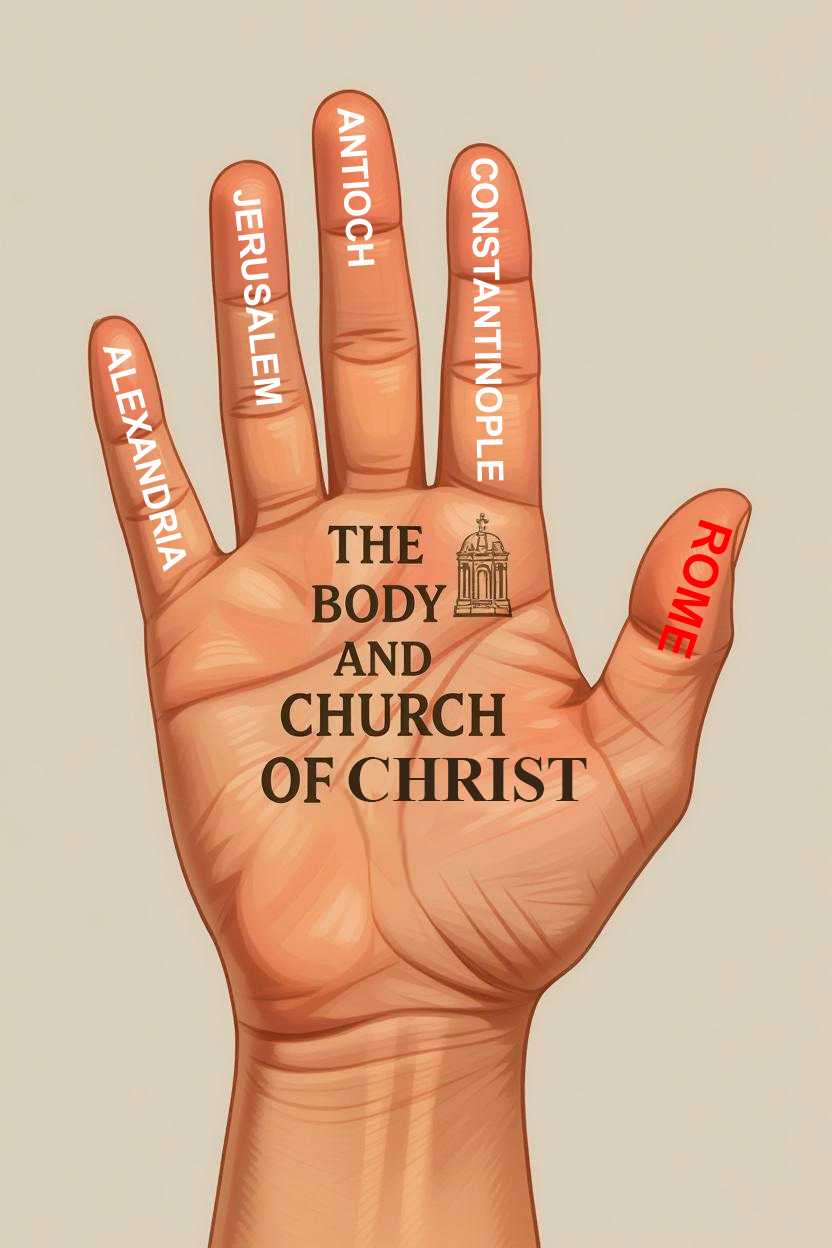

Ok, this is the 5-minute, simple kindergarten version. For this I’m going to use the analogy of a hand. It’s not perfect, but it will do.

Let’s pretend that the early church, the initial body of Christ is a hand with four fingers and a thumb. Each digit represents one of the primary Patriarchates that existed in the first millenia. You can see my wonderful attempts at art below that illustrates this concept. Why did I put Rome on the thumb and not the index finger? Because Rome was all the way out in the West, somewhat isolated geographically from the other patriarchates. The other four were relatively close to each other and maintained more regular correspondence.

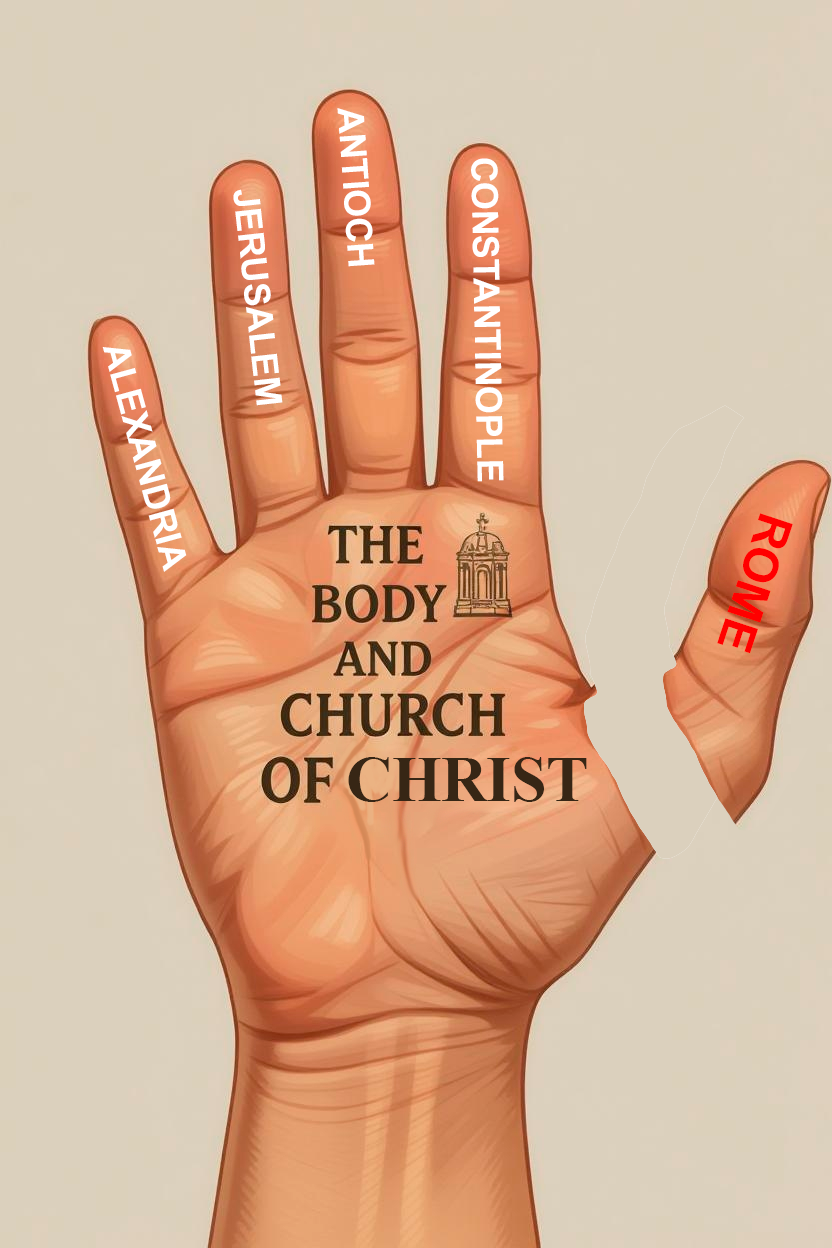

Then, Rome decides to excommunicate the Patriarch of Constantinople, who was more or less the defacto seat of the East being that Constantinople was the seat of the byzantine Empire. This separates Rome from the rest of the patriarchates. This gives us the following updated image.

In this image, who can rightfully retain or lay claim to the hand? The now detached thumb or the fingers that remain?

Aftermath

Initially, the 1054 events were not widely recognized as a permanent split; chroniclers of the time barely noted them, and diplomatic relations between Rome and Constantinople continued, including alliances during the Crusades. However, tensions escalated in the following centuries, particularly after the sack of Constantinople by Roman Catholic Crusaders in 1204, which deepened mutual distrust. By the 13th century, the divide had solidified into two distinct traditions.

The excommunications did not target the other eastern patriarchates, Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria, however, they were under heavy Byzantine political and ecclesiastical influence so as the split hardened, they aligned with Constantinople.

The schism’s legacy persists today, with the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches remaining separate, though ecumenical efforts since the 20th century (e.g., the lifting of mutual excommunications in 1965 by Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras) have fostered dialogue. It represents not just a religious rupture but a profound cultural and geopolitical shift in Christianity.

While there are many who are hopeful for a reunification of East and West in my opinion it will never happen. Why?

The East will insist on removing the filioque.

The East will insist on a rejection of all doctrinal developments since 1054, which I just don’t see the Latins agreeing to, it would fundamentally change their religion and I don't think Roman Catholics would want that either.

E.G. immaculate conception, the sacred heart, adoration of the gifts, papal infallibility, papal supremacy, enforced celibacy of priests, etc.

Post Schism Identity

The Great Schism of 1054 marked the formal separation between the Eastern Orthodox Church (centered in Constantinople) and the Roman Catholic Church (centered in Rome.) Eastern Orthodox people sometimes refer to the Roman Catholic Church as the Latin Church and roman catholics as “the latins.” (Which I have done here.)

Today, in the West, someone hearing the word “Catholic” will typically associate it with the Roman Catholic Church. However, technically, both divisions (East and West) are the Catholic Church. What we are really talking about is a church split, so when we say Roman Catholic, what we are really saying is the portion of the Catholic Church centered in Rome (i.e., the Patriarchate of Rome). When we refer to Eastern Orthodox, we are actually referring to the other patriarchates of the original Catholic Church that remained in the Eastern Empire. (Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, and, err, Alexandria.) You may also see the East refer to itself with the more technically precise name “The Orthodox Catholic Church.” This has nothing to do with the “Catholic Church” that we all think of as centered in Rome with the Pope.

Why does the East use the word Orthodox to describe itself?

“Orthodox” means “correct belief” or “right worship” in Greek (from orthos = correct, doxa = belief or glory). This emphasizes their belief that they have preserved the original, apostolic Christian faith as defined by the early ecumenical councils, especially in opposition to what they consider heresies or deviations by the Latins.

The name “Orthodox Catholic Church” highlights both its claim to the “right faith” and its continuity as the “universal” (catholic) Church from the earliest Christian era. The “Eastern” part of the name reflects only the geographical and cultural origins in the eastern Mediterranean and Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire).

The Eastern Church distinguished itself from the Latin Church after the Schism by adopting the term “Orthodox” to affirm its fidelity to early Christian doctrine and practices, particularly as defined by the first seven ecumenical councils.

Aside: What did you mean by, “err, Alexandria” above?

The patriarchate of Alexandria split, and one part separated itself after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD (The fourth ecumenical council). There was a disagreement about the nature of Christ, referred to as the Miaphysite dispute. The Council of Chalcedon affirmed the position that Christ was one person with two natures (human and divine). This is called the hypostatic union; hypostasis means “person” or “individual existence.” The council articulated that Christ has two natures, Divine and Human, in one person. If you ever hear someone say that Christ is fully God and fully Man, this is what they are referring to.

Those who rejected Chalcedon, known as Miaphysites, held that Christ had only one nature, which is both fully divine and fully human.

The council condemned as heresy what is called the monophysite heresy, that Christ possesses one single divine nature, and that his human nature was absorbed or diminished by his divine nature. Everyone condemned this view.

So why did they break away? IT seems to have been a misunderstanding of linguistic terms. They disagreed with the specific language and theological implications of the Chalcedonian definition. They believed this language risked dividing Christ into two persons (a form of Nestorianism), which they saw as a grave error.

After Chalcedon, the Patriarchate of Alexandria split into two groups: the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria (which we will henceforth refer to as Alexandria which remained in communion with the other churches) and the non-Chalcedonian faction, which, together with several Eastern churches (including those in Egypt, Syria, and Armenia, including some under the jurisdictions of Antioch and Jerusalem) refused to accept the Chalcedonian definition and eventually became known as the Oriental Orthodox churches. The non-Chalcedonian faction remaining in Alexandria is known as the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.

Political and cultural tensions also contributed to this split. At the time of the Chalcedonian schism, several churches were attempting to resist encroaching Byzantine political control that sought to impose religious and cultural uniformity. Thus, the schism was at least in part an assertion of nationalist and cultural identity, driven by resentment of perceived imperial control and oppression. The split between Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox has never been healed despite numerous attempts.

Hopefully this puts and end to the who left who debate.